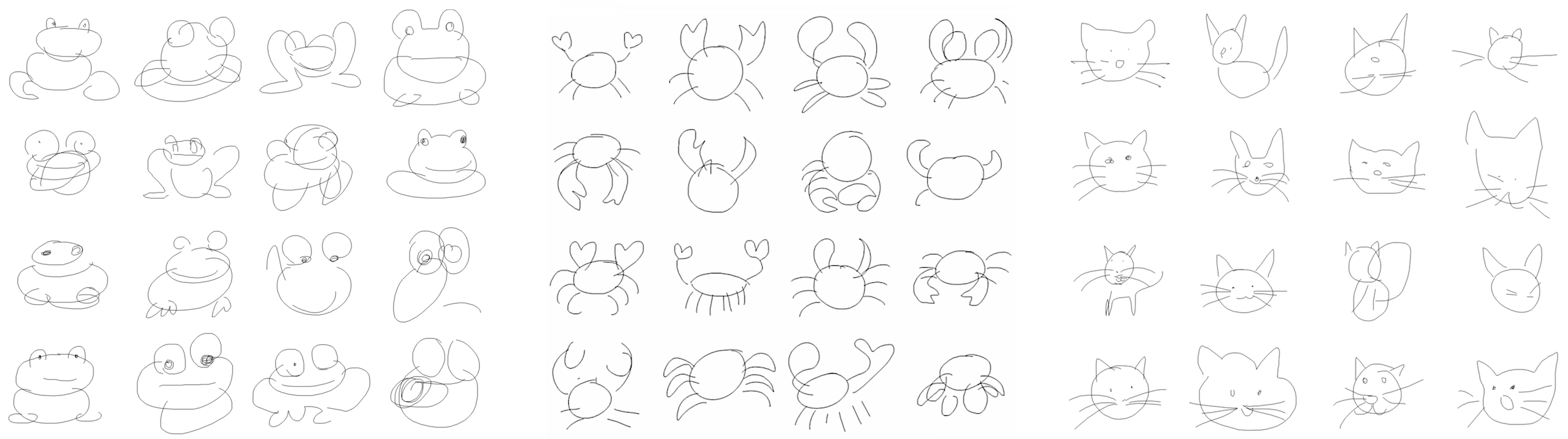

Latent space interpolation of various vector drawings produced by

Latent space interpolation of various vector drawings produced by sketch-rnn.

GitHub

This is an updated version of my article, cross-posted on the Google Research Blog. Instructions on using the sketch-rnn model is available at Google Brain Magenta Project. Link to our paper, “A Neural Representation of Sketch Drawings”. This article has also been translated to Simplified Chinese.

Introduction

Vector drawings produced by our model.

Vector drawings produced by our model.

Recently, there have been major advancements in generative modelling of images using neural networks as a generative tool. While there is a already a large body of existing work on generative modelling of images using neural networks, most of the work thus far has been targeted towards modelling low resolution, pixel images.

Humans, however, do not understand the world as a grid of pixels, but rather develop abstract concepts to represent what we see. From a young age, we develop the ability to communicate what we see by drawing on a piece of paper with a pencil. In this way we learn to express a sequential, vector representation of an image as a short sequence of strokes. In this work, we investigate an alternative to traditional pixel image modelling approaches, and propose a generative model for vector images.

Children learn to draw Doraemon as a sequential set of strokes.Humans learn to draw sequentially. Designers rely on vector graphics. Yet most ML Research focus only on generative models for pixel images. pic.twitter.com/3VHe3HmFCi

— hardmaru (@hardmaru) May 20, 2017

Children develop the ability to depict objects, and arguably even emotions, with only a few pen strokes. They learn to draw their favourite anime characters, family, friends and familiar places. These simple drawings may not resemble reality as captured by a photograph, but they do tell us something about how people represent and reconstruct images of the world around them.

“The function of vision is to update the internal model of the world inside our head, but what we put on a piece of paper is the internal model.”

In our paper, “A Neural Representation of Sketch Drawings”, we present a generative recurrent neural network capable of producing sketches of common objects, with the goal of training a machine to draw and generalize abstract concepts in a manner similar to humans. We train our model on a dataset of hand-drawn sketches, each represented as a sequence of motor actions controlling a pen: which direction to move, when to lift the pen up, and when to stop drawing. In doing so, we created a model that potentially has many applications, from assisting the creative process of an artist, to helping teach students how to draw.

In this work, we model a vector-based representation of images inspired by how people draw. We use recurrent neural networks as our generative model. Not only can our recurrent neural network generate individual vector drawings by constructing a sequence of strokes, like these previous experiments on Generative Handwriting and Generative Kanji, our model can also generate a vector drawing conditional on a latent vector, , as an input into the model.

Similar to a previous work where we interpolate between multiple latent vectors to generate animated high-resolution morphing MNIST animations, we can train our model on hand-drawn sketches from the yoga category of the QuickDraw dataset, and have it dream up yoga positions in both time and space directions.

“Generating sequential data is the closest computers get to dreaming.”An RNN's Understanding of Yoga. pic.twitter.com/0E4AJ3B49X

— hardmaru (@hardmaru) April 14, 2017

A Generative Model for Vector Drawings

Our model, sketch-rnn, is based on the sequence-to-sequence (seq2seq) autoencoder framework. It incorporates variational inference and utilizes Hyper Networks as recurrent neural network cells. The goal of a seq2seq autoencoder is to train a network to encode an input sequence into a vector of floating point numbers, called a latent vector, and from this latent vector reconstruct an output sequence using a decoder that replicates the input sequence as closely as possible.

Schematic of

Schematic of sketch-rnn.

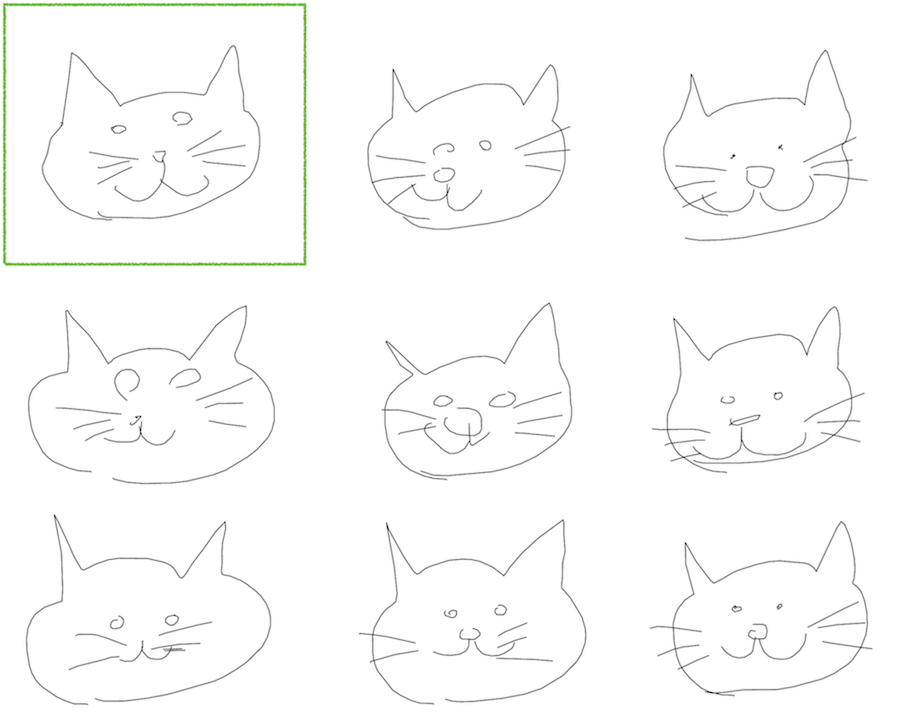

In our model, we deliberately add noise to the latent vector. In our paper, we show that by inducing noise into the communication channel between the encoder and the decoder, the model is no longer be able to reproduce the input sketch exactly, but instead must learn to capture the essence of the sketch as a noisy latent vector. Our decoder takes this latent vector and produces a sequence of motor actions used to construct a new sketch. In the figure below, we feed several actual sketches of cats into the encoder to produce reconstructed sketches using the decoder.

Reconstructions from a model trained on cat sketches sampled at varying temperature levels.

It is important to emphasize that the reconstructed cat sketches are not copies of the input sketches, but are instead new sketches of cats with similar characteristics as the inputs. To demonstrate that the model is not simply copying from the input sequence, and that it actually learned something about the way people draw cats, we can try to feed in non-standard sketches into the encoder. When we feed in a sketch of a three-eyed cat, the model generates a similar looking cat that has two eyes instead, suggesting that our model has learned that cats usually only have two eyes.

To show that our model is not simply choosing the closest normal-looking cat from a large collection of memorized cat-sketches, we can try to input something totally different, like a sketch of a toothbrush. We see that the network generates a cat-like figure with long whiskers that mimics the features and orientation of the toothbrush. This suggests that the network has learned to encode an input sketch into a set of abstract cat-concepts embedded into the latent vector, and is also able to reconstruct an entirely new sketch based on this latent vector.

Not convinced? We repeat the experiment again on a model trained on pig sketches and arrive at similar conclusions. When presented with an eight-legged pig, the model generates a similar pig with only four legs. If we feed a truck into the pig-drawing model, we get a pig that looks a bit like the truck.

Reconstructions from a model trained on pig sketches sampled at varying temperature levels.

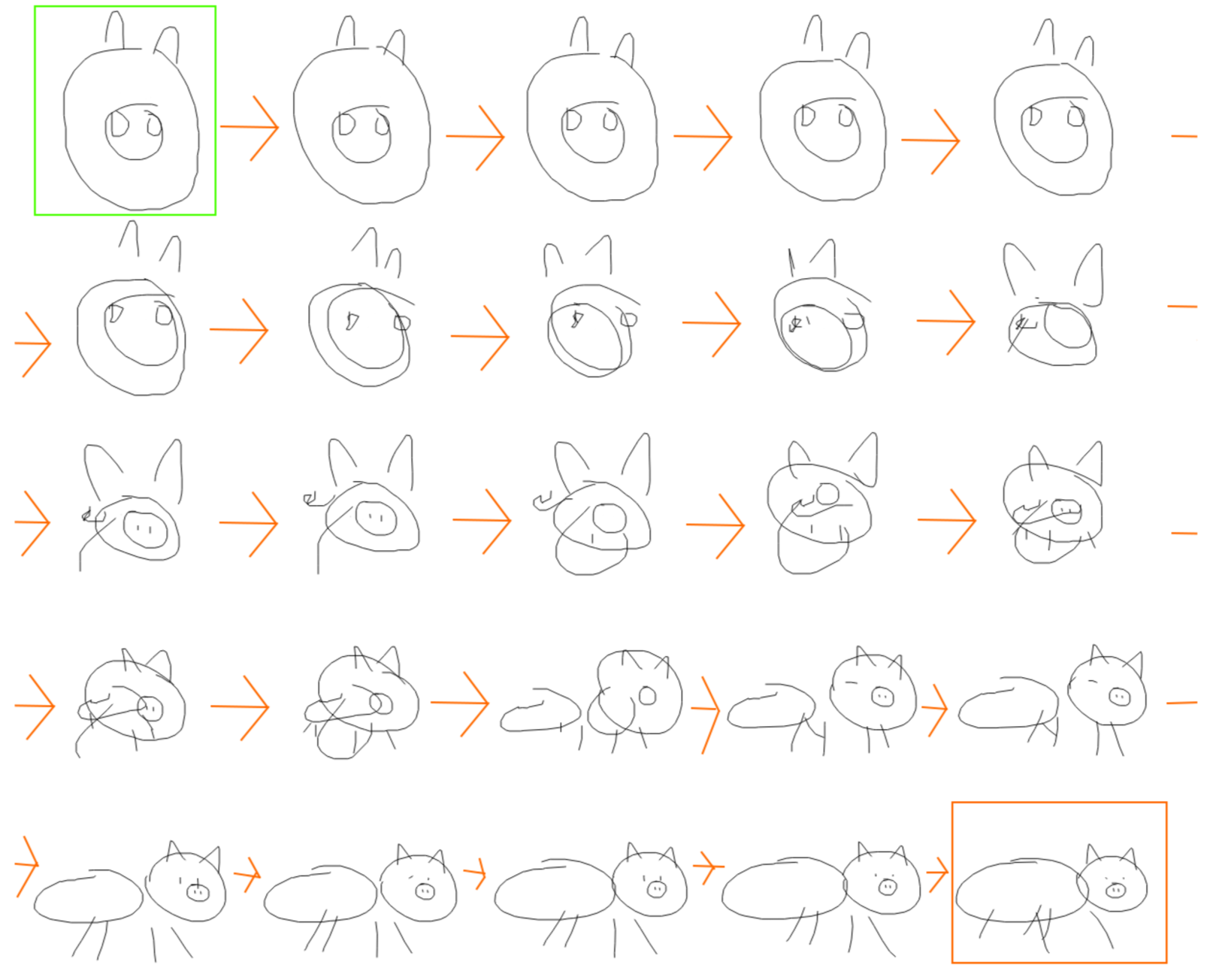

To investigate how these latent vectors encode conceptual animal features, in the figure below, we first obtain two latent vectors encoded from two very different pigs, in this case a pig head (in the green box) and a full pig (in the orange box). We want to get a sense of how our model learned to represent pigs, and one way to do this is to interpolate between the two different latent vectors, and visualize each generated sketch from each interpolated latent vector. In the figure below, we visualize how the sketch of the pig head slowly morphs into the sketch of the full pig, and in the process show how the model organizes the concepts of pig sketches. We see that the latent vector controls the relatively position and size of the nose relative to the head, and also the existence of the body and legs in the sketch.

Latent space interpolations generated from a model trained on pig sketches.

We would also like to know if our model can learn representations of multiple animals, and if so, what would they look like? In the figure below, we generate sketches from interpolating latent vectors between a cat head and a full pig. We see how the representation slowly transitions from a cat head, to a cat with a tail, to a cat with a fat body, and finally into a full pig. Like a child learning to draw animals, our model learns to construct animals by attaching a head, feet, and a tail to its body. We see that the model is also able to draw cat heads that are distinct from pig heads.

Latent Space Interpolations from a model trained on sketches of both cats and pigs.

These interpolation examples suggest that the latent vectors indeed encode conceptual features of a sketch. But can we use these features to augment other sketches without such features - for example, adding a body to a cat’s head?

Learned relationships between abstract concepts, explored using latent vector arithmetic.

Indeed, we find that sketch drawing analogies are possible for our model trained on both cat and pig sketches. For example, we can subtract the latent vector of an encoded pig head from the latent vector of a full pig, to arrive at a vector that represents the concept of a body. Adding this difference to the latent vector of a cat head results in a full cat (i.e. cat head + body = full cat). These drawing analogies allow us to explore how the model organizes its latent space to represent different concepts in the manifold of generated sketches.

Creative Applications

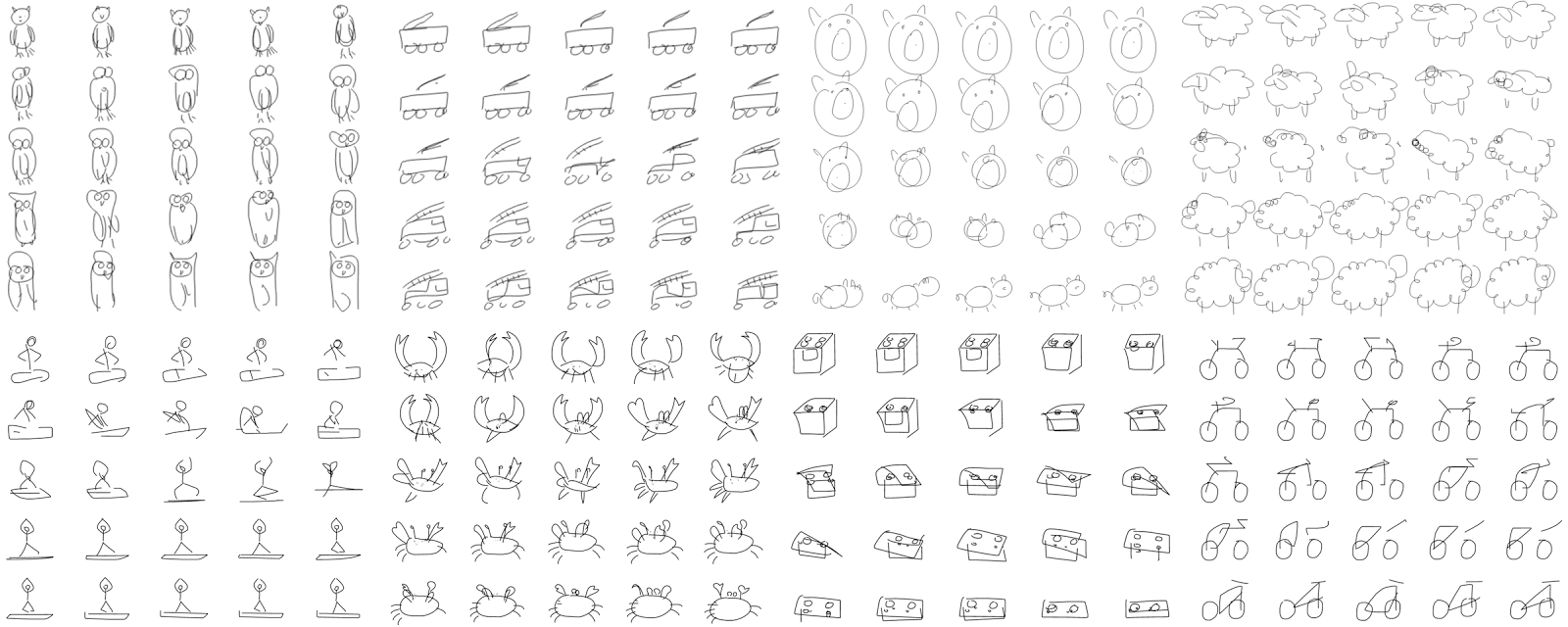

Exploring the latent space of generated sketches of everyday objects.

Latent space interpolation from left to right, and then top to bottom.

In addition to the research component of this work, we are also super excited about potential creative applications of sketch-rnn. For instance, even in the simplest use case, pattern designers can apply sketch-rnn to generate a large number of similar, but unique designs for textile or wallpaper prints.

As we saw earlier, a model trained to draw pigs can be made to draw pig-like trucks if given an input sketch of a truck. We can extend this result to applications that might help creative designers come up with abstract designs that can resonate more with their target audience.

Similar, but unique cats, generated from a single input sketch in the greenbox (left).

Exploring the latent space of generated chair-cats (right).

For instance, in the earlier figure above, we feed sketches of four different chairs into our cat-drawing model to produce four chair-like cats. We can go further and incorporate the interpolation methodology described earlier to explore the latent space of chair-like cats, and produce a large grid of generated designs to select from.

Exploring the latent space between different objects can potentially enable creative designers to find interesting intersections and relationships between different drawings:

Exploring the latent space between cats and buses, elephants and pigs, and various owls.

We can also use the decoder module of sketch-rnn as a standalone model and train it to predict different possible endings of incomplete sketches. This technique can lead to applications where the model assists the creative process of an artist by suggesting alternative ways to finish an incomplete sketch. In the figure below, we draw different incomplete sketches (in red), and have the model come up with different possible ways to complete the drawings.

The model can start with incomplete sketches and automatically generate different completions.

We believe the best creative works will not be created only with machines, but possibly by designers who use machine learning as a tool to enrich their creative thinking process. In the future, we envision how these tools can be used collaboratively with artists and designers. Below is a simple conceptual example illustrating this collaboration using our model:

“Making it rain with recurrent neural nets.”

We are very excited about the future possibilities of generative vector image modelling. These models will enable many exciting new creative applications in a variety of different directions. They can also serve as a tool to help us improve our understanding of our own creative thought processes. Learn more about sketch-rnn by reading our paper, “A Neural Representation of Sketch Drawings”.

Citation

If you find this work useful, please cite it as:

@article{ha2017neural,

title={A neural representation of sketch drawings},

author={Ha, David and Eck, Douglas},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.03477},

year={2017}

}