In this post, I will talk about our recent paper called Hypernetworks. I worked on this paper as a Google Brain Resident - a great research program where we can work on machine learning research for a whole year, with a salary and benefits! The Brain team is now accepting applications for the 2017 program: see g.co/brainresidency. This article has also been translated to Simplified Chinese.

Introduction

A Dynamic Hypernetwork Generating Handwriting.

The weight matrices of the LSTM are changing over time.

Most modern neural network architectures are either a deep ConvNet, or a long RNN, or some combination of the two. These two architectures seem to be at opposite ends of a spectrum. Recurrent Networks can be viewed as a really deep feed forward network with the identical weights at each layer (this is called weight-tying). A deep ConvNet allows each layer to be different. But perhaps the two are related somehow. Every year, the winning ImageNet models get deeper and deeper. Think about a deep 110-layer, or even 1001-layer Residual Network architectures we keep hearing about. Do all 110 layers have to be unique? Are most layers even useful?

Figure: Feed forward network, no weight sharing (top). Recurrent network, weight sharing (bottom).

People have already thought of forcing a deep ConvNet to be like an RNN, i.e. with identical weights at every layer. However, if we force a deep ResNet to have its weight tied, the performance would be embarrassing. In our paper, we use HyperNetworks to explore a middle ground - to enforce a relaxed version of weight-tying. A HyperNetwork is just a small network that generates the weights of a much larger network, like the weights of a deep ResNet, effectively parameterizing the weights of each layer of the ResNet. We can use hypernetwork to explore the tradeoff between the model’s expressivity versus how much we tie the weights of a deep ConvNet. It is kind of like applying compression to an image, and being able to adjust how much compression we want to use, except here, the images are the weights of a deep ConvNet.

While neural net compression is a nice topic, I am more interested to do things that are a bit more against the grain, as you know from reading my previous blog posts. There are many algorithms that already take a fully trained network, and then apply compression methods to the weights of the pre-trained network so that it can be stored with fewer bits. While these approaches are useful, I find it much more interesting to start from a small number of parameters, and learn to construct larger and complex representations from them. Many beautiful complex patterns in the natural world can be constructed using a small set of simple rules. Digital artists have also designed beautiful generative works based on this concept. It is this type of complex-abstraction concept that I want to explore in my machine learning research. In my view, neural network decompression is a more interesting problem than compression. In particular, I also want to explore decompressing the weights of an already compressed neural net, i.e., the weights of a recurrent network.

The more exciting work is in the second part of my paper where we apply Hypernetworks to Recurrent Networks. The weights of an RNN are tied at each time-step, limiting its expressivity. What if we can have a way to allow the weights of an RNN to be different at each time step (like a deep convnet), and also for each individual input sequence?

Figure: Static Hypernetwork generates weights for Feedforward Network.

Figure: Dynamic Hypernetwork generates weights for Recurrent Network.

The main result in the paper is to challenge the weight-sharing paradigm of Recurrent Nets. We do this by embedding a small Hypernetwork inside a large LSTM, so that the weights used by the main LSTM can be modified accordingly by the Hypernetwork, whenever it feels like modifying the weights. In this instance, the Hypernetwork is also another LSTM, just a smaller version, and we will give it the power to modify the weights of the main LSTM, at each timestep, and also for each input sequence. In the process, we achieve state-of-the-art results for character level language modelling tasks for Penn Treebank and Wikipedia datasets. More importantly, we explore what happens when our models are able to generate generative models.

The resulting HyperLSTM model looks and feels like a normal generic TensorFlow RNN cell. Just like how some people among us have super-human powers, in the HyperLSTM model, if the main LSTM is a human brain, then the HyperLSTM is some weird intelligent creature controlling the brain from within.

I, for one, welcome our new Arquillian overlords.

Background

The concept of using a neural network to generate the weights of a much larger neural network originated from Neuroevolution. While genetic algorithms are easy and fun to use, it is difficult to get them to directly find solutions for a really large set of model parameters. Ken Stanley came up with a brilliant method called HyperNEAT to address this problem. He came up with this method while trying to use an algorithm called NEAT to create beautiful neural network generated art. NEAT is an evolved neural network that can be used to generate art by giving it the locations of each pixel and reading from its output the colour of that pixel. What if we get NEAT to paint the weights of a weight matrix instead? HyperNEAT attempts to do this. It uses a small NEAT network to generate all the weight parameters of a large neural network. The small NEAT network usually consists of less than a few thousand parameters, and its architecture evolved to produce the weights of a large network, given a set of virtual coordinate information about each weight connection.

While the concept of parameterizing a large set of weights into a small number of parameters is indeed very useful in Neuroevolution, some other researchers thought that HyperNEAT can be a bit of an overkill. Writing and debugging NEAT can be a lot of work, and selective laziness can go a long way in research. Schmidhuber’s group decided to try an alternative method, and just use Discrete Cosine Transform to compress a large weight matrix so that it can be approximated by a small set of coefficients (this is how JPEG compression works). They then use genetic algorithms to solve for the best set of coefficients so that the weights of a recurrent network is good enough to drive a virtual car around the tracks inside the TORCS simulation. They basically performed JPEG compression on the weight matrix of a self-driving car.

Some people, including my colleagues at Deepmind have also played around with the idea of using HyperNEAT to evolve a small weight-generating network, but use back propagation instead of genetic algorithms to solve for the weights for the small network. They summarized some cool results in their paper about DPPNs.

Personally, I’m more interested to explore another aspect of neural network weight generation. I like to view a neural net as a powerful type of computing device, and the weights of the neural net are kind of like the machine-level instructions for this computer. The larger the number of neurons, the more expressive the neural net becomes. But unlike machine instructions of a normal computer, neural network weights are also robust, so if we add noise to some part of the neural network, it can still function somewhat. For this reason I find the concept of expressing a large set of weights with a small number of parameters fascinating. This form of weight-abstraction is sort of like coming up with a beautiful abstract higher level language (like LISP or Python) that gets compiled into raw machine-level code (the neural network weights). Or from a biological viewpoint, it is also like how large complex biological structures can be expressed at the genotype level.

Static Hypernetworks

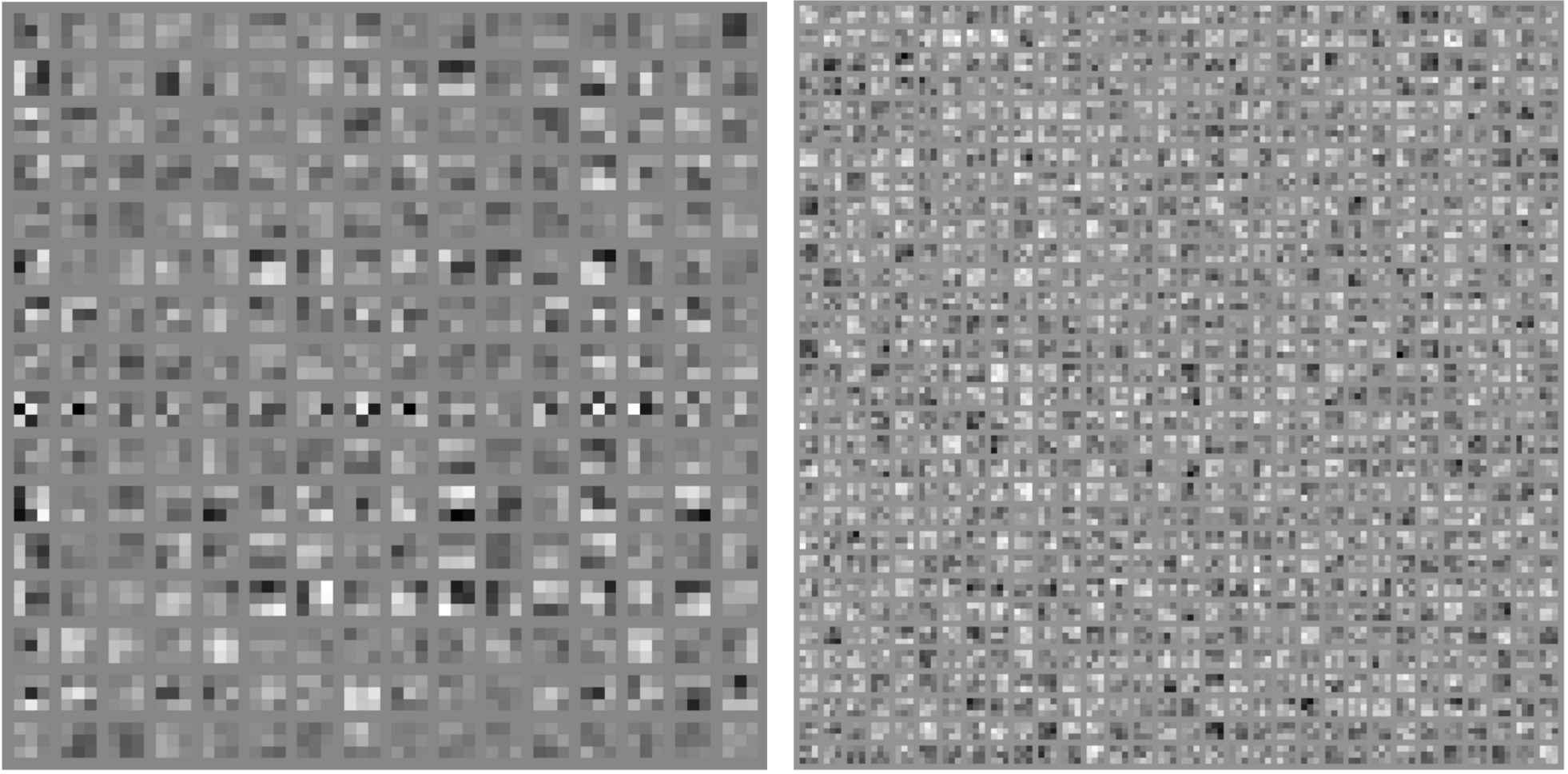

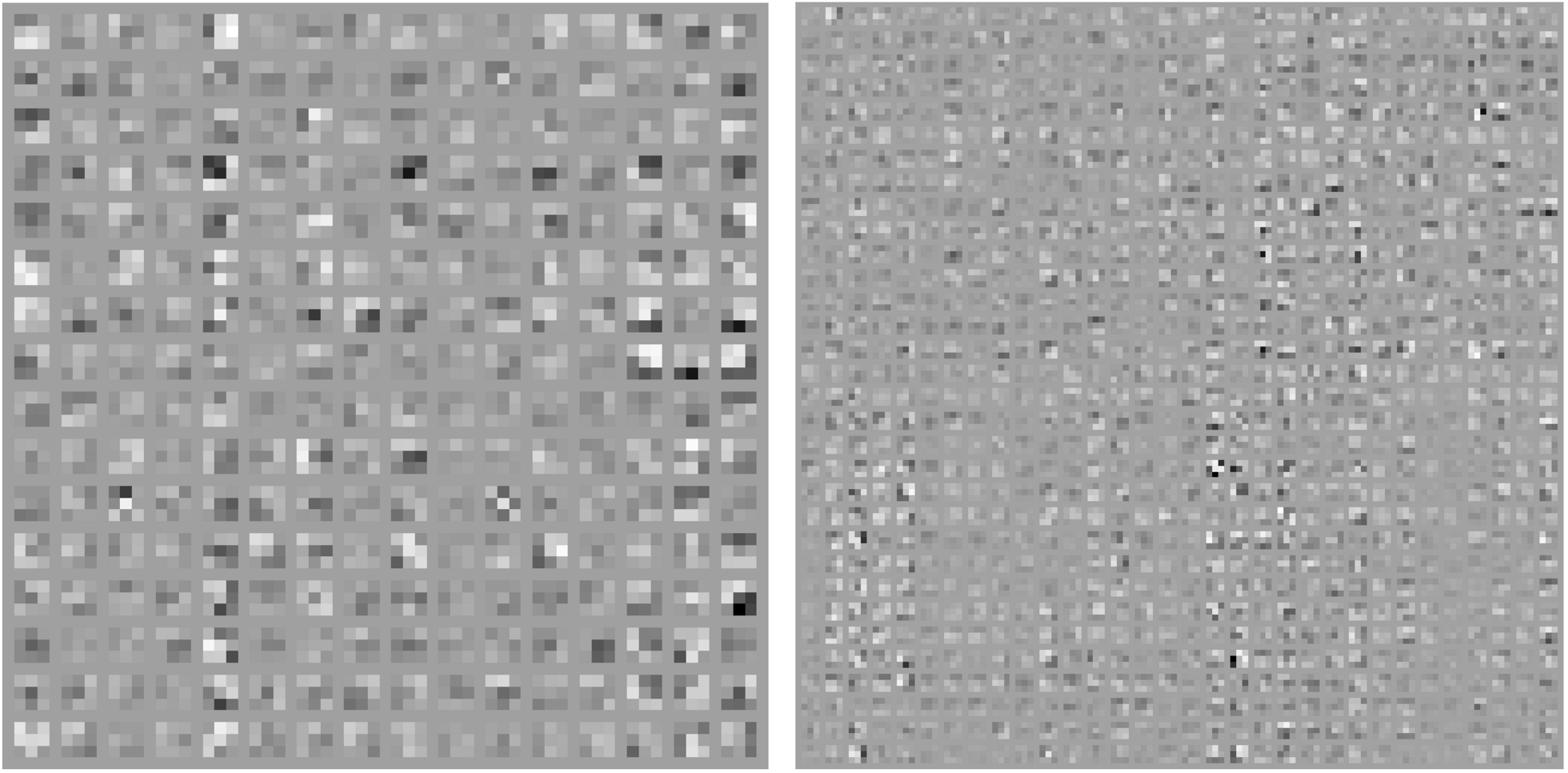

In the paper, I decided to explore the concept of having a network to generate weights for a larger network, and try to develop this concept a bit further. However, I took a slightly different approach from HyperNEAT and DPPNs. As mentioned above, these methods take a set of virtual input coordinates as input to a small network to generate the weights of a large network. I played around with this concept extensively (See Appendix Section A of the paper), but it just didn’t work well for modern architectures like deep ConvNets and LSTMs. While HyperNEAT and DCT can produce good looking weight matrices, due to the prior enforced by smooth functions such as sinusoids, this artistic smoothness is also its limitation for many practical applications. A good looking weight matrix is not useful if it doesn’t work. Look at this picture of the weights of a typical Deep Residual Network:

Figure: Images of a 16x16x3x3, and 32x32x3x3 Weight Kernels in typical Residual Network trained on CIFAR-10.

While I won’t want to hang pictures of ResNet weights in my living room wall, they work really well, and I want to generate pictures of these weights with less parameters. I took an approach that is simpler and more in the fashion of VAE or GAN-type approaches. More modern generative models like GANs and VAEs take in a smallish embedding vector Z, of say 64 numbers, and from these 64 values, try to generate realistic images of cats or other cool things. Why not also try to generate weight matrices for a ResNet? So the approach we take is also to train a simple 2-layer network to generate the 16x16x3x3 weight kernels with an embedding vector of 64 numbers. The larger weight kernels will just be constructed by tiling small versions together (ie, the one on the right will require 256 numbers to generate). We will use the same 2-layer network to generate each and every kernel of a deep ResNet. When we train the ResNet to do image classification, rather than training the ResNet weights directly, we will be training the set of Z’s and the parameters of this 2-layer network instead.

Figure: Images of generated 16x16x3x3, and 32x32x3x3 Weight Kernels for a ResNet trained on the same task.

We experimented with a typical off-the-shelf ResNet (the “WRN-40-2” configuration from this nice ResNet variation called Wide Residual Networks), of which 36 layers are these types of weight kernels. The best test classification accuracy on CIFAR-10 at the time of writing is ~ 96% using tens of millions of parameters. This particular ResNet uses only ~ 2.2 million parameters and can be trained to get ~ 94% accuracy on CIFAR-10, which I think is quite good. Our version of this ResNet that uses hypernet-generated weights used merely ~ 150k parameters, while the accuracy is still respectable. Our model got ~ 93% test accuracy.

Figure: Structure of the Wide ResNet Family. We used N=6 and k=2.

These results makes me think about these super deep 1001 layer ResNets that perform really well on ImageNet contests. Perhaps most of their weights are not that useful, but actually having the weights there, as a kind of placeholder, so that a large number of neurons can compute is the useful bit of why they are so good.

If you would like to see an implementation, please see this IPython Notebook prepared to demonstrate this weight-generation concept outlined in the MNIST experiment in the paper. The notebook can be extended and combined with the Residual Network model in TensorFlow.

Dynamic Hypernetworks

As mentioned in the Introduction, we also tried to apply Hypernetworks on Recurrent Networks, and I feel this is the main contribution of the research. One of the insights from working with hypernetworks on ResNets is that while we get to use much fewer parameters in the model, we see a reduction of accuracy as a tradeoff. So what if we go the other way instead? If we can use a hypernetwork to allow us to relax the weight-sharing constraints of an RNN, and allow the weight matrix to change at each unrolled timestep, it would look closer like a deep ConvNet, so maybe we can squeeze better results from them.

Figure: The HyperRNN system. The black system represents the main RNN while the orange system represents the weight-generating HyperRNN cell.

Our approach is to put a small LSTM cell (called the HyperLSTM cell) inside a large LSTM cell (the main LSTM). The HyperLSTM cell will have its own hidden units and its own input sequence. The input sequence for the HyperLSTM cell will be constructed from 2 sources: the previous hidden states of the main LSTM concatenated with the actual input sequence of the main LSTM. The outputs of the HyperLSTM cell will be the embedding vector Z that will then be used to generate the weight matrix for the main LSTM.

Unlike the Static Hypernetwork, the weight-generating embedding vectors are not kept constant, but will be dynamically generated by the HyperLSTM cell. This allows our model to generate a new set of weights at each time step and for each input example. In the paper I discuss many practicalities and more computationally and memory efficient approach of generating the weights from the embedding vector to simplify and reduce computation constraints of this approach. One thing that I learned is that while it is important to dream up new types of algorithms and new approaches in research, at the end of the day it is important to keep things practical and make stuff work. It is also important to make it easy for other people to use your work.

For our implementation of Dynamic Hypernetworks, we made it so that we can just plug our HyperLSTM cell into any TensorFlow code written to use tf.nn.rnn_cell objects, since the HyperLSTM inherited from this abstract class. This makes it easy to plug my research code to existing code that was designed to use the vanilla LSTM cell. For example, when I was experimenting with our HyperLSTM cell on the wikipedia dataset, I just used char-rnn-tensorflow and plugged the research model right in for training and inference. Here is a passage that char-rnn-tensorflow generated with our HyperLSTM model after training on the wikipedia enwik8 dataset:

Figure: Generated text, along with levels of weight-changing activity of the main LSTM’s weight matrices. Somehow HyperLSTM learned to put Soviet, Facism, a computer company, and an all-important type of machine in one sentence.

In the above figure, in addition to just displaying the generated text, we can also visualise how the weights of the main LSTM are being modified by the HyperLSTM cell. I chose to visualise the changes of the four hidden-to-gate weight matrices of the LSTM over time in four different colours, to represent each of the four input, candidate, forget and output gates of the LSTM (see this blog post for a great explanation). We can interpret high intensity regions as instances where the HyperLSTM cell just made large changes to the weights of the main LSTM, before the main LSTM is used to generate each character. A low intensity means the HyperLSTM cell is taking a break, so the weights of the main LSTM are not being changed that much during these breaks. Below is another example passage:

An interesting thing to note is during the less active periods of the HyperLSTM cell, the types of words seem to be more predictable. For example, from the first example, Microsoft Windows was generated by more or less a static network after Micros. In the second example, elections in the early 1980s was generated by a relatively constant main LSTM, but right after the 1980s, the HyperLSTM cell suddenly woke up and decided to give the main LSTM model a bit of a shake, before it went to discuss savage employment concerns. In a way, the HyperLSTM cell is generating the generative model as the generative model is generating the sequence.

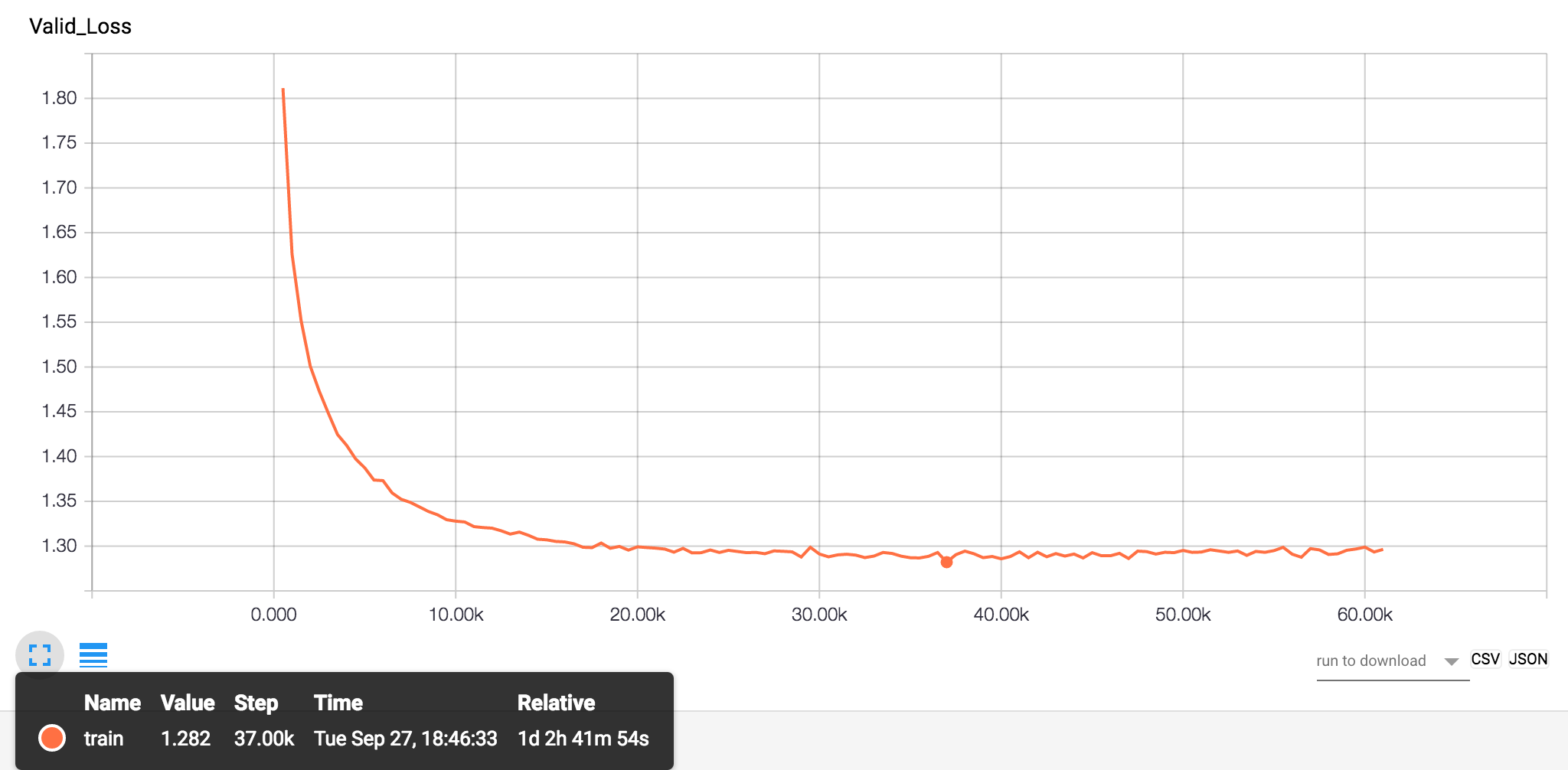

This meta-ability to dynamically generate the generative model seems to be very powerful, and in fact our HyperLSTM model was able to beat previous state-of-the-art character-level prediction dataset benchmarks such as Character-Level Penn Treebank and Hutter Prize Wikipedia (enwik8). Our model got 1.25 bpc and 1.38 bpc respectively (as of 27-Sep-2016) without using dynamic evaluation, beating previous records of 1.27 and 1.40 (as of 10-Sep-2016).

Someone else will probably beat these state-of-the-art numbers in a few weeks given the fast pace of the machine learning research field, and also the fact that ICLR 2017 deadlines are just around the corner. In fact, I don’t really think beating the state-of-the-art on some text dataset is as important as exploring the concept of this multi-level dynamic model within a dynamic model abstraction. I think in the future, people might focus less on architecture design, and the focus will move towards two directions, either towards the application side, or more towards the fundamental building block side. The thing I like about our approach is we effectively created a building block called the HyperLSTM, which from the TensorFlow user’s point of view, looks and feels like exactly like a normal LSTM cell. It is just as easy to plug-and-play the HyperLSTM into existing TensorFlow code, as changing between RNN, GRU, and LSTM cells, since we made HyperLSTM to be just an instance oftf.nn.rnn_cell.RNNCell, called HyperLSTMCell (which contains the full system, not to be confused with the HyperLSTM Cell).

Generating Generative Models

I also experimented HyperLSTM to perform the handwriting generation task. In a previous post, I explored Alex Graves’ approach of getting an LSTM to generate a random handwriting sequence. The way this generation works is to model the and coordinates of the pen stroke as a 2D mixture Gaussian distribution, along with a binary Bernoulli random variable to model the probability that the pen stays on the paper.

Figure: Handwriting sampled from a 2D mixture Gaussian distribution, and the Bernoulli distribution, using the vanilla LSTM model. Both the Gaussian and Bernoulli probability distributions change over time.

During handwriting, the parameters of these two distributions will change over time, and also depend on each other. For example, as you are finish writing a word, the probability that your pen leave the paper increases, and the next location of the pen will likely be further away from where it is now and have a much higher variance. We can get an LSTM to output the parameters for both the mixture Gaussian and the Bernoulli distribution, and have the values of these parameters change at each timestep depending on the LSTM’s internal states. You can visualize how the Gaussian distribution changes over time by looking at the red bubbles in the above figure, which indicate the location and size of the Gaussian distributions for next pen stroke. We can sample from this time-varying distribution and hence sample an entire fake handwriting passage by connecting the sampled points. I view this type of model to be similar to Dynamic Hypernetworks, since an LSTM is dynamically changing the parameters of a generative distribution (the Gaussian and the Bernoulli) over time, and by training the entire model on a handwriting dataset, it can perform a formidable job of generating handwriting samples.

In our paper, we applied Dynamic Hypernetworks to extend this approach. We will replace BasicLSTMCell in my code with HyperLSTMCell. In this approach, the weight matrices and biases of the LSTM will be modified over time by a smaller LSTM. By doing this simple change, we extend this model-generating-model approach by another level, by having a small LSTM dynamically generate a larger LSTM model at each time step, and for the generated large LSTM model to generate parameters for the Gaussian and Bernoulli distributions also at each time step. So model-generating-model becomes model-generating-model-generating-model.

Similar to text-generation earlier, this newer approach achieves much better scores compared to the normal, and even multi-layer LSTM’s, with a similar number of training parameters. I modified write-rnn-tensorflow to replicate the exact experiment done in section 4.2 of Graves’ paper, and checked that the Log Loss results when using BasicLSTMCell is similar enough to the previously published results. After tying out with the previous historical results, we can switch BasicLSTMCell to HyperLSTMCell and rerun the experiments. But before doing that, we tried to improve our baseline method first. It is important show the baseline technique some respect, and give face to them, since they led way to our research. We found that applying black magic techniques like data-augmentation and dropout, we can already improve the scores for the baseline 1-Layer BasicLSTMCell from -1026 nats to -1055 nats. After switching on our model, the HyperLSTMCell got the Log Loss score all the way down to -1162 nats, a large and meaningful improvement. Along with the quantitative results are various actual generated samples from various models you can check out in the paper (in the Appendix section).

To wrap up this post, I made a small demo showing how the handwriting generation process works with HyperLSTMs. I want to show how the weights of the main LSTM is being modified by the HyperLSTM cell with this demo. Unlike character-generation, the time-axis doesn’t really correspond exactly to the x-axis for handwriting, so I found it easier to visualise this process as a web-demo, since you can’t really do animations for .pdf papers submitted to arXiv. In the future, more science will move more towards web-posts rather than static .pdf files for journals and conferences. My colleagues @ch402 and @shancarter also recently created a platform called distill.pub to encourage the more modern web-based publication format. I will start using this platform in the future.

You can see the handwriting being generated as well as changes being made to the LSTM’s 4 hidden-to-gate weight matrices. I chose to only visualize the changes made to , , , of the main LSTM in the four different colours, although in principle , , , and all the biases can also be visualized as well. Higher intensity means the HyperLSTM cell is making a larger modification to the weights of the main LSTM. You can see that large changes typically take place between characters and words, despite the network not being told explicitly what the concept of a written character let alone a written word is. Both LSTM and HyperLSTM had to work together to figure out these concepts on their own.

Local Implementation

I learned a lot from reading open-source code and tutorials, and for practical Recurrent Networks in TensorFlow I highly recommend Denny Britz’s blog, the mysterious r2rt super-blog, this blog post on Recurrent Batch Norm, and also TensorFlow With The Latest Papers Implemented.

This local implementation of HyperLSTMCell is based on the Layer Norm implementation by LeavesBreathe and Batch Norm code by OlavHN. You can also try to plug HyperLSTMCell into char-rnn-tensorflow, or use in other interesting tasks. It works, but currently is not as fast as vanilla LSTM, but over time I expect to see many improvements in core TensorFlow that allow for more speedy optimisations.

Figure: TensorBoard Results for Character PTB Validation Set (BPC versus training step).

HyperLSTMCell

TensorFlow implementation at https://github.com/hardmaru/supercell/.

Citation

If you find this work useful, please cite it as:

@article{ha2016hypernetworks,

title={Hypernetworks},

author={Ha, David and Dai, Andrew and Le, Quoc V},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.09106},

year={2016}

}